Industrial MBRs − ship effluents

Membrane bioreactors in the marine sector

In the marine industry, discharge restrictions are legislated according to MARPOL (Marine Pollution Convention), the IMO (International Maritime Organisation) convention for the prevention of pollution from ships, including sewage.

Sewage, or 'black water', refers to discharges from the toilets and urinals and the onboard hospital. 'Grey water' refers to discharges from showers, wash basins, laundries, and galley operations. 'Bilge water', which contains high oil concentrations, rust and detergents, is usually treated separately.

The sewage in ships is collected by either gravity or vacuum systems. Most use fresh water for toilet flushing to reduce corrosion, and vacuum toilets are preferred on the basis of the reduced water demand of 1.1−1.4 L per flush compared to 4.9 L for water-saving, high-efficiency land-based domestic toilets. The vacuum toilet system has two direct impacts on shipboard sewage characteristics:

- the hydraulic loading is low at 15−25 L/day/person compared with the quantity of waste discharged by individuals in the US at 190 to 460 L/day/person on land

- black water is consequently much higher in strength (TSS, COD, BOD and other chemical constituents) than municipal wastewater. Ammonia concentrations can reach 500−1,000 mg N-NH4/L.

Grey waters generated from the accommodation, laundries, the on-board hospital and galleys are also collected by their own dedicated piping systems and holding tanks. Grey water has 10 times the black water flow. It can have very high organic load and FOG content due to galley operations (there are typically 5−8 restaurants on a cruise ship, for example).

Treating black and grey water on ships

The different water source characteristics support the notion of separate treatment streams, rather than a combined black/grey water stream, though the latter tends to be favoured by many shipboard sewage treatment suppliers.

Unlike land-based sewage treatment, the design of marine effluent systems is constrained by:

- the confined space for installation and operation

- the high strength of the waste

- extreme and variable hydraulic and organic shock loads

- vibration, and

- the requirement for robustness associated with the remote location.

The advantages of segregated processing of the black and grey water become more apparent in global regions where regulations are more stringent, making separate biological treatment of the high-nutrient black water waste stream more viable.

Conventional sewage treatment plants on ships comprise physical/chemical and biological treatment, each having their own characteristics.

Physical/chemical treatment may be based on physical methods like:

- comminuting/maceration

- screening, and

- sedimentation

as well as chemical methods including:

- advanced oxidation

- coagulation

- flocculation, and

- disinfection.

These provide a relatively small footprint because of the shorter retention time compared with biotreatment. However, reliance on chemical dosing limits their application on large ships due to the chemical handling and storage issues, along with the associated sludge production.

Using MBRs to treat ship effluent

Since around the early 1990s, a number of advanced biological municipal wastewater treatment technologies have been adapted and developed for marine applications. These have included the sequencing batch reactor (SBR), the moving bed bioreactor (MBBR) and, following research from the mid 1990s onwards, the MBR.

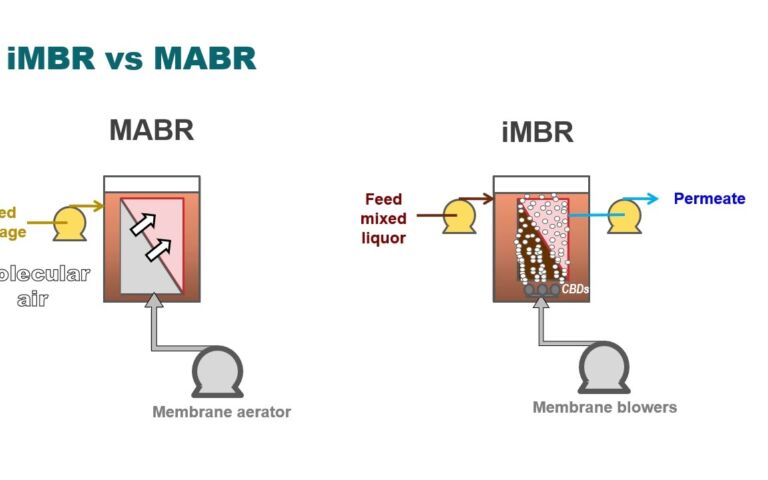

In general, biotreatment technologies are based on either non-barrier systems (such as SBRs and MBBRs) with ultraviolet irradiation (UV) or membrane filtration for downstream disinfection, or else comprise membrane bioreactors (MBRs) for single-step biotreatment and disinfection.

Some of the original MBR technologies were based on the sidestream configuration (sMBRs). However, an increasing number are now based on the immersed configuration.