PVDF membranes and PFAS: what impact of the EU’s REACH legislation?

Dr Graeme Pearce

Graeme is Director at Membrane Consultancy Associates Ltd. He is a membrane technology specialist with 40 years experience in the membrane industry. Email: [email protected]

1. PFAS pollutants and PVDF membranes: the connection

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) arise in a vast array of products. In the membrane industry, the most common material used is PVDF, which could be classed as a PFAS compound since it is produced from PFAS monomers.

Potential restrictions on PFAS levels in water present a double-edged sword for the membrane industry. On one hand, a new target contaminant offers a new purification opportunity. However, the membrane itself may fall foul of the restrictions. Membranes, and PVDF specifically, can potentially leach components or break down to PFAS chemicals thereby contributing to PFAS contamination.

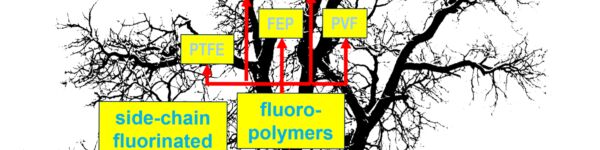

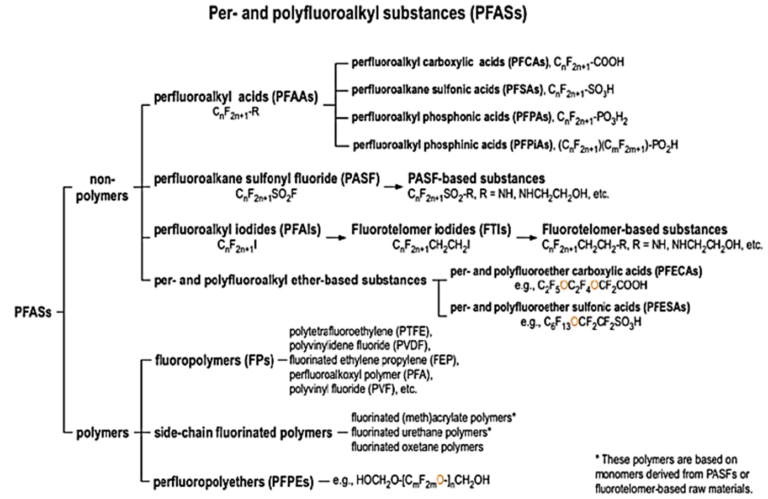

The OECD-produced family tree of PFAS substances (see below), referenced by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), includes PVDF. Some commentators are more selective in their PFAS definition, but the tree indicates that PFAS encompasses fluoropolymers used for membranes.

2. Legislative approaches: US vs EU

While the EPA has focused on the effect of PFAS chemicals on health and the environment, the EU has targeted the production and use of these chemicals through extending existing regulations.

In 2006, the EU introduced REACH regulations (Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and restriction of Chemicals) covering all aspects of the use of chemicals within EU member states. At that time, these regulations posed a threat to membrane manufacture in Europe due to restriction or control of the use of certain solvents used in membrane manufacture. It took a decade before the regulation was meaningfully enforced, but ultimately EU manufacturers were able to accommodate and comply with the restrictions. Whilst the legislation imposed greater barriers for new entrants setting up facilities for membrane manufacturing in Europe, it did not impact on the choice of PVDF as a membrane material.

Some fluorinated chemicals (such as PFOS, perfluorooctane sulfonic acid) were restricted under the original proposals and subsequent revisions, but the effects on PVDF membranes were limited. However, a dramatic new development proposes to extend the chemicals covered by REACH to include all PFAS compounds and is now out for consultation - due to report in September 2023. Under this proposal the manufacture and use of PFAS in Europe would be banned.

If adopted in full, REACH would mark the beginning of the end for membranes such as PVDF made from fluorinated polymers. Derogations may be granted for some PFAS chemicals in cases where there is deemed to be no alternative, but these would likely be time-limited over a number of years.

There is a marked contrast in the approaches from either side of the Atlantic. The US EPA has taken a cautious and relatively business-friendly approach to PFAS, deeming that compounds are acceptable until toxicity data prove otherwise: compounds are considered ‘innocent until proven guilty’. The EU, on the other hand, is taking the precautionary approach of aiming to remove the whole class of PFAS compounds unless the benefits of retaining identified compounds for specific uses outweigh the advantages of removal: in effect, ‘guilty until proven innocent’. Both approaches have the same goal but are tackling the problem from perspectives that are polar opposites.

3. Threats and impacts

So does the threat from stable polymers such as the PVDF used in membranes justify such Draconian control, or are the EU perhaps over-REACHing? Let’s look at the three key impacts: commercial, health and environmental.

3.1 Commercial impacts

The commercial importance of PVDF is clear. Two thirds of the current membrane filtration market for potable water uses PVDF. Hollow fibre PVDF membrane manufacture is concentrated amongst relatively few suppliers who operate internationally, having an established presence in the key European and US markets. Such companies would be profoundly impacted by a ban, with policy pronouncements in Europe inevitably shaping decisions in the US. Whilst alternative polymers are feasible for the European membrane market, PVDF membranes have dominated the US membrane water filtration market for the past 25 years.

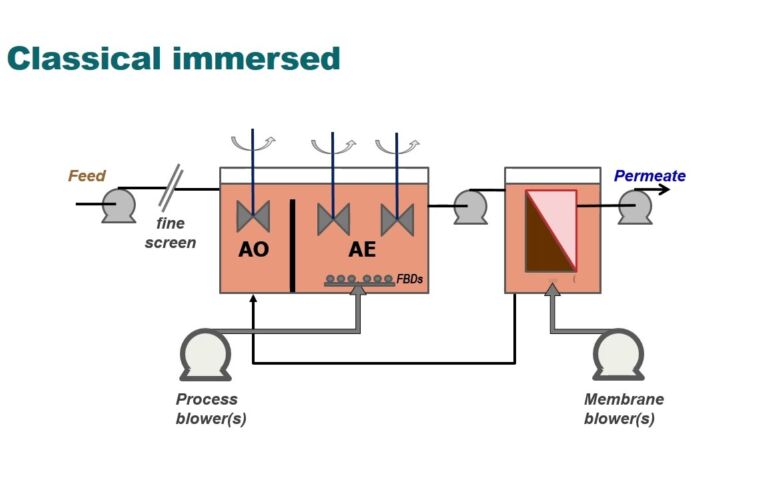

PVDF is also used for MBR technology in both hollow fibre and flat sheet formats. Companies in this area would have to rethink their strategies since PVDF is even more dominant here than in the potable water sector. Chinese manufacturers have a strong position in MBR technology and many products are made solely for use within their domestic market. Although the China local market might not be affected in the short term, the re-structuring of the world order will surely impact Chinese manufacturers.

Outside of these uses for water/wastewater filtration, PVDF is used as a component for other membrane applications in water treatment - for example as a flat sheet support in spiral wound products.

In summary, PVDF is used widely in commercial membrane products globally. In terms of its technical performance, it would be extremely hard to replace.

3.2 Human health impacts

The choice of PVDF as a membrane material is associated primarily with its stability. The PVDF polymer is made from a fluorinated monomer. The resulting polymer is made into a membrane. The membrane gradually degrades during its life in terms of its mechanical strength, but leaching tests conducted for drinking water approval imply no leaching of monomers or molecular fragments injurious to health (except potentially as micro-plastics, but this is a different issue).

It can be concluded that the use of PVDF as a membrane material is unlikely to adversely affect human health.

3.3 Environmental impacts

Adverse environmental impacts may potentially arise during manufacture, but since manufacture takes place in a series of isolated environments these risks can be controlled.

During use, any environmental risk is negligible since PVDF membranes are chemically stable and leaching of PFAS chemicals specifically insignificant.

The most significant environmental risk is at end-of-life of the membrane, as disposal through incineration or landfill will ultimately impact the environment. This could potentially be mitigated by recycling, but this option has not been considered viable due to fears of cross-contamination.

A possible consequence of REACH for PVDF membranes is that manufacturing and disposal will be effectively off-shored, i.e. moved outside of the EU, while ‘use’ may continue to be permitted - at least for a time.

4. Implications and consequences

It’s clear that the EU proposals would have implications for PVDF membranes. In the short term, other materials such as PES could benefit - and it may accelerate the recent trend towards the use of ceramics.

It is possible that there will be pushback which would allow PVDF membrane manufacture to continue under close scrutiny. The fluoropolymer representative industrial body (FPP4EU, the FluoroProducts and PFAS for Europe group which represents producers, importers, and users of fluorinated products and PFAS across Europe) has issued a six-point action plan (see below), which includes derogations in key applications which are not time limited.

This is a big ask and it will take solid persuasion to prove that PVDF does no harm in the membrane context using current data. More realistically, PVDF membrane makers need to at least have a defined plan by September 2023 to build the case for demonstrating that PVDF is acceptable and the rewards and benefits of using it outweigh any potential risks. This could potentially be combined with a timeline and/or a planned and phased change to alternative non-PFAS materials.

| Proposed action | Justification for proposed action | FPP view |

|---|---|---|

| Improve the understanding of PFAS uses to prevent supply chain disruptions and elimination of important products and applications | The current proposal, whilst detailed, reflects only a fraction of the current uses of PFAS. There is no existing tracking system that provides information about PFAS along the whole supply chain. Many product manufacturers may unknowingly place on the market non-PFAS containing products that rely on PFAS in their production process. | FPP4EU will compile a non-exhaustive list of generic uses not covered by the proposal and identify potential impacts this restriction may have on some (currently unforeseen) critical uses. As stakes are high for many applications and there are no alternatives currently identified for many uses of PFAS, we also ask the authorities to allow sufficient time to hear all concerned stakeholders, clarify data requirements, and ensure adequate time to review all data. |

| Exempt PFAS used in industrial settings | The properties of many PFAS substances are often the reason that they are used. They can withstand harsh conditions such as high voltage and temperatures, corrosiveness or chemical interactions. It means that they are absolutely crucial to use in pipes and vessels transporting highly corrosive chemicals or solvents, to prevent accidents and protect workers. For example, PFAS coating is key for the safe transport of liquid hydrogen, protecting the integrity of the pipes from the degradation of mechanical properties. | FPP4EU asks to consider an exemption for those PFAS used in industrial settings, potentially with additional reporting and management plan obligations to ensure emissions from the use of PFAS are minimised. |

| When assessing PFAS, keep their differences in mind | The list of PFAS includes over 10,000 substances. Not all PFAS are equal, many have very different properties and they do not all have the same effects on health and environment. | FFP4EU has designed a decision tree that provides elements that can be considered when discussing exemptions. It includes a risk assessment phase which takes into account that PFAS can have completely different hazard profiles. |

| Address economic impacts of the proposal along with the entire value chain | The current proposal addresses the use of PFAS in the final products and applications as well as the use of PFAS in the manufacturing stage. Restricting uses of certain PFAS may have knock-on effects on non-restricted uses of the same PFAS substances or products produced with them, as a low production volume may not justify continued manufacture. This could result in these non-restricted or exempted products disappearing in European value chains. Some companies may go out of business if they can’t use PFAS to manufacture their products within the EU, even in some cases where the products do not even contain a PFAS. | FPP4EU proposes an impact assessment is undertaken to establish the financial implications of the restriction proposal. |

| Consider the important of PFAS in achieving the European policy objectives | Some PFAS substances are indispensable to reach the objectives set out in various EU policy initiatives such as the EU pharmaceuticals strategy, the new Industrial Strategy, the European Chips Act, the EU Strategic Action Plan on Batteries or the EU strategy on hydrogen, just to name a few. For instance, applications such as electric vehicles, renewable energy production, energy storage or hydrogen pipes, rely on the performance and functionality of PFAS. While the search for alternatives may accelerate, the typical time scale of the R&D process – from discovery to commercial scale up – is at least a decade, especially for high-end sophisticated applications. | It is vital to allow sufficient transition time to search for and test the potential alternatives in Europe that offer the same combination of properties, but may have a better environmental footprint. |

| Ensure the PFAS restriction is enforceable | Evidence has shown that imported goods are the largest source of non-compliance with EU chemicals and product safety laws. Enforcing a restriction targeting thousands of substances will be very challenging and extremely difficult to achieve. | To better enforce the PFAS restriction, FPP4EU would recommend to (a) standardise and fund development of analytical methods to detect PFAS in products and consider the availability of these methods when setting transition periods, and (b) put in place measures and processes to improve the enforcement of the restriction at the borders. |

5. Conclusion

There is little doubt that we are in for a decade of fundamental change for the membrane filtration industry. While the proposed legislation currently affects only Europe, the shockwaves are likely to be felt globally.

Engagement and negotiation will be essential if the reign of PVDF membranes is to be extended. As alluded to by the FPP, PFAS actually manifestly contribute positively to achieving key sustainability goals (electric vehicles, the hydrogen economy and, of course, water reuse). In the case of PVDF membranes, it is debatable whether the significant benefits offered by their use are negated by the environmental risk incurred from their end disposal. It is perhaps the management of the latter that demands attention, rather than banning the material itself.