The joy of text − academic research papers

Simon Judd has over 35 years’ post-doctorate experience in all aspects of water and wastewater treatment technology, both in academic and industrial R&D. He has (co-)authored six book titles and over 200 peer-reviewed publications in water and wastewater treatment.

One of the joys of being an academic is that we are tasked with writing papers. We are also expected to review papers, although this is supposed to be done outside office hours in what is laughingly called ‘free time’.

There seems to be an unwritten law which states you are expected to review 3−5 times the number of submitted papers as the number of papers you write. I’m sure all academics will be familiar with that particular quid pro quo. So, having co-authored a fair few papers myself, it is indeed the case that I’ve reviewed a great many more. The experience has provided a number of insights into writing patterns − and specifically clichés − which perhaps may interest the more discerning readers of this blog.

It should be stated upfront that this is in no way intended to be viewed as a visceral attack on my academic brethren. It is written in the spirit of improving the mental welfare of those of us who choose to spend our ‘free time’ on reviewing journal papers and, by happy consequence, may also help reduce my blood pressure.

Cliché no. 1: This won’t come as a surprise to anyone but the cliché I rail against the most is, ‘membrane fouling is the most significant challenge to MBR implementation’. Anyone who has read this blog will know my view on this (so, don’t get me started). Suffice to say that, so far as municipal wastewater is concerned, this statement is factually incorrect.

Cliché no. 2: Almost as infuriating is: ‘this [technology, technique …] offers much promise for wastewater treatment in the future’. This manages to tick three boxes at once in that it is (a) aspecific, (b) hackneyed, and (c) almost certainly untrue − unless the ‘promise’ is to go the way of most other bench-scale tests reported in the academic literature.

State of the art: But to my mind, the greatest sin in academic writing − and one which seems to be the modus operandi for a number of authors (or so it would seem) − is failing to show any evidence of having read the recently published papers relating to their work. I’m not sure whether this is ignorance or intentional, but in my experience too many academic papers fail to demonstrate a grasp of the state of the art, even to the extent of overlooking the actual commercial implementation of some technologies.

To demonstrate the point, authors of recently submitted academic research papers I’ve seen have cited the following as novel concepts:

- mechanical shear for enhancing membrane separations

- immersed anaerobic MBRs, and

- phosphorus recovery.

The employees of New Logic (V-Sep), Evoqua (ADI’s AnMBR) and Ostara, to name but three, may be a little perturbed that their technologies have gone apparently unnoticed by some sections of the academic community.

But this also extends to acknowledging the work of their own research peers when submitting papers.

Take, for example, anaerobic MBRs which have been commercialised for the last 25 years (in the case of the sidestream technology) and which have not exactly been criminally neglected by the academic community. And yet I’ve recently reviewed a few papers that have completely overlooked the dozen-or-so review articles − let alone the hundreds of scientific and technical studies − published on this topic over the past 5−6 years.

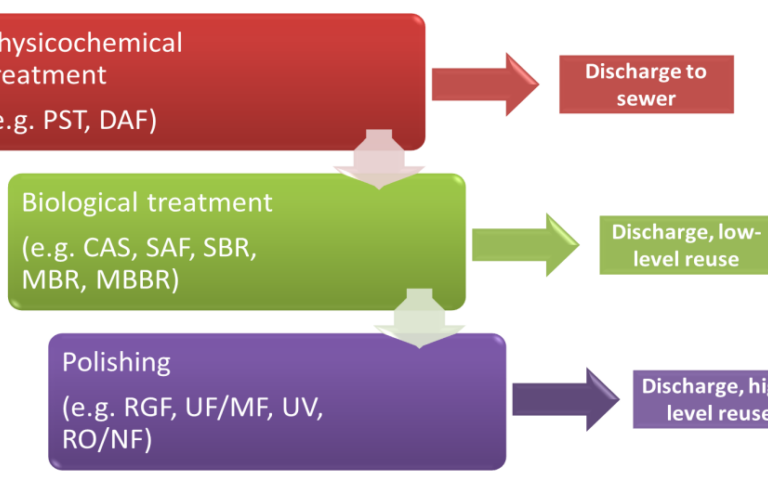

Really, though, this is all quite literally academic. The purpose of the swathes of academic journals is ultimately to inform the community of the state of the art. And in the case of wastewater treatment, the ultimate beneficiaries should be the practitioners whose job it is to keep the technology running. But maybe sometimes it cuts the other way.

I was in conversation with a WwTW operator the other week who went into great detail as to the havoc wreaked by sanitary towels at his works, and the remedial measures needed. Most of it is unrepeatable but, suffice to say, any woman inclined to dispose of feminine hygiene products via the toilet would probably benefit from a conversation with this guy.

Which is to say that, probably a lot of the challenging, not to say pretty unsavoury, issues at WwTWs could be successfully addressed by better source control. This means effective education to change habits, specifically of treating the toilet as a trash can.

If the academic community really did want something to ‘offer much promise for wastewater treatment in the future’, then this would be right up there with zero-energy/zero-waste treatment. And if research really is meant to address current and future challenges, then maybe a more comprehensive knowledge of the actual practical challenges is needed.

But then, does changing habits count as research? Probably not. Academic research should be ground-breaking, novel and (sic) innovative. God forbid that it should ever simply be useful.