What can go wrong with an MBR?

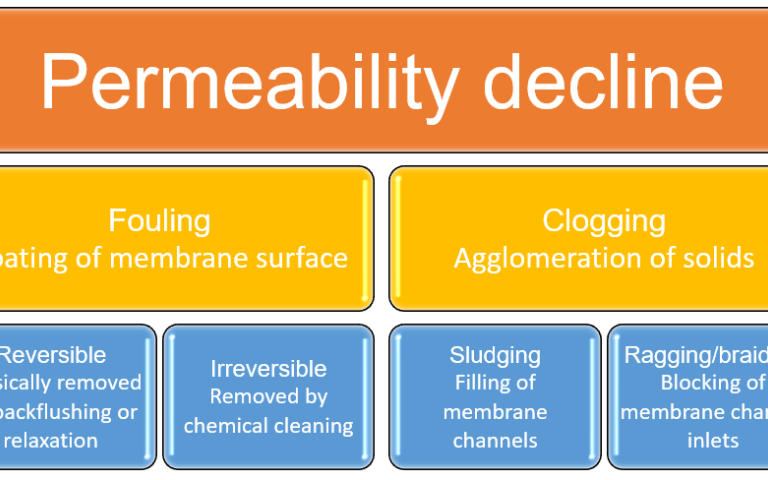

As with most other wastewater treatment processes, a design which is not conservative enough can impair the routine operation of the plant and lead to widely recognised technical challenges of membrane surface fouling and, in particular, membrane channel clogging.