Membrane science – a geek writes

Simon Judd has over 35 years’ post-doctorate experience in all aspects of water and wastewater treatment technology, both in academic and industrial R&D. He has (co-)authored six book titles and over 200 peer-reviewed publications in water and wastewater treatment.

The less generous souls among us may regard membrane scientists as being a little geeky. This is slanderous: no self-respecting geek would ever wish to be associated with membrane science. Most people would run a mile rather than engage in conversation with a physicist. And then run a further 10 miles to avoid a chemist. But with membrane science, you have both physicists and chemists: the physics covering the likes of film theory, hydraulic resistance and molecular dynamics, and the chemistry for chemical/biochemical stoichiometry, organic polymer synthesis and Gibbs–Donnan equilibria. Oh yes, membrane science is pretty hard core.

While I’ve no rooted objection to science per se (my educational background is in science, after all – I am a severely lapsed chemist) – it’s technology which puts science to good use. So, the forthcoming International Membrane Science & Technology Conference (‘IMSTEC’) would seem to cover all bases.

I last attended IMSTEC more than a decade ago, in Sydney. And, come February of next year, I’ll be doing the same thing: same conference and, completely coincidentally, same city. I am, naturally, massively looking forward to it.

IMSTEC is very broad-based: anything membrane separation-related is fair game. In focusing on membranes specifically, it differs from most conferences which are based on application (drinking water, wastewater, pulp and paper applications, whatever…), but this is not without its merits. The fact is that a membrane is a simple enough thing: it’s a piece of material with very small holes. And pretty much the same material can be used for removing bacteria from milk, crystallization of pharmaceutical compounds, or concentrating sludge solids.

So, why not just focus on the membrane process, and lump all the applications together in a single meeting?

Of course, there are some persuasive reasons for disconnecting pure water from wastewater applications within an organisation. Different target water quality parameters apply and, certainly within the municipal sector, different legislative processes.

But, as others have noted, the fundamentals of the separation process don’t change with the application. The main defining process parameter is always the flux, the permeation energy consumption is governed largely by the transmembrane pressure (and for immersed processes, the air scour rate), and the membrane always needs to be cleaned. Plus, pretreatment is always required.

Dense membrane processes like reverse osmosis and nanofiltration may differ substantially in configuration to porous ones like ultrafiltration and microfiltration, but the same principle applies: whether it’s seawater that’s being desalinated or mains water being demineralised, the same key parameters of flux, pressure and conversion govern process operation. And, again, the membranes always need to be cleaned and the process protected by pretreatment.

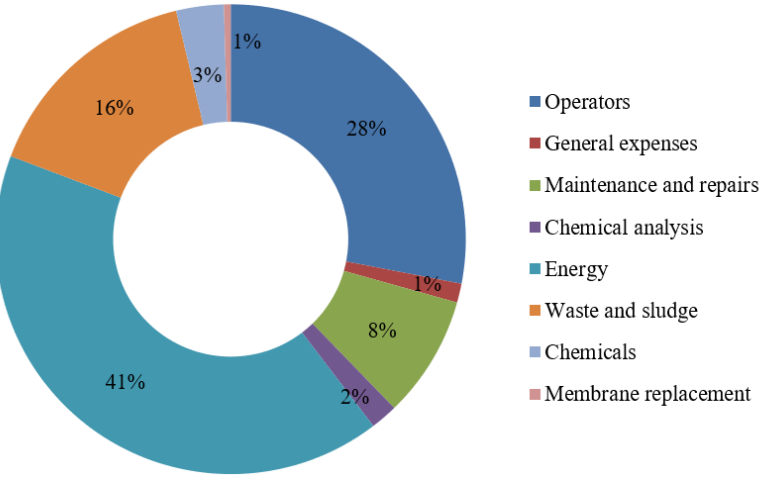

The key difference between applications and sectors is the value of the water produced. There are a lot of unit operation steps involved in generating process water for the production of pharmaceuticals, for example. But the cost incurred by this is justified by the purity of the water demanded and, ultimately, the value of the product.

And that’s where the innovation comes. Sure, we already have plenty of membranes that will do the job – but if they can be produced more cheaply, made more reliable and/or last longer than whatever’s available for a specific application then there’s always likely to be a market for them.

And it pays not to be too dismissive. At a conference I recently attended there was a guy generating membranes from a 3D printer. It seemed completely idiotic to me: it must take a fair while to generate the thousands of m2 membrane needed to treat a moderate flow of wastewater.

But then, a lot of people thought Kazuo Yamamoto was mad to place a membrane in a tank full of thick, gloopy activated sludge to extract the water. Perhaps not very scientific, but that technology seems to have done rather well.

IMSTEC ran from 2nd until 6th February 2020, at the UTS Aerial Convention Centre https://www.imstec2020.com/