When MBR sludge goes bad

Simon Judd

Simon Judd is author of The MBR Book (Elsevier, 2010)

1. Introduction

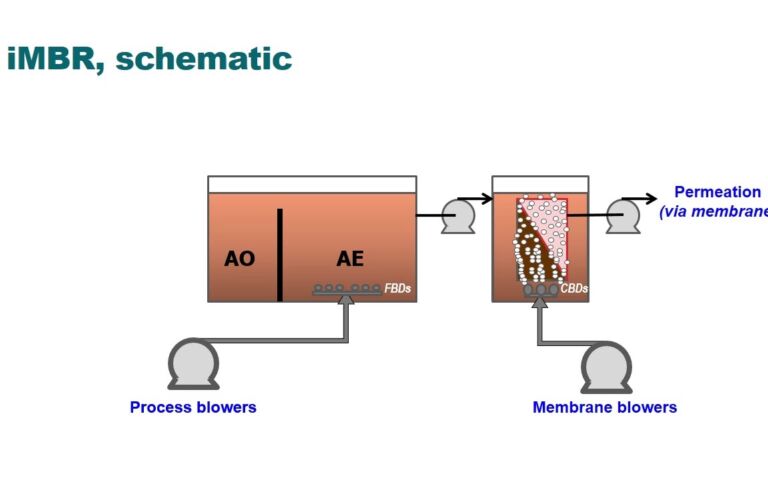

Membrane bioreactors (MBRs) are generally recognised as providing a high quality effluent for either discharge to environmentally sensitive waters, or for recycling purposes. The implementation of this technology has grown considerably over the past fifteen years, largely driven by increasingly stringent constraints placed on effluent water quality. However, they are technically limited by the tendency of the throughput to diminish as a result of processes occurring at or near the membrane surface.

2. Fouling and clogging

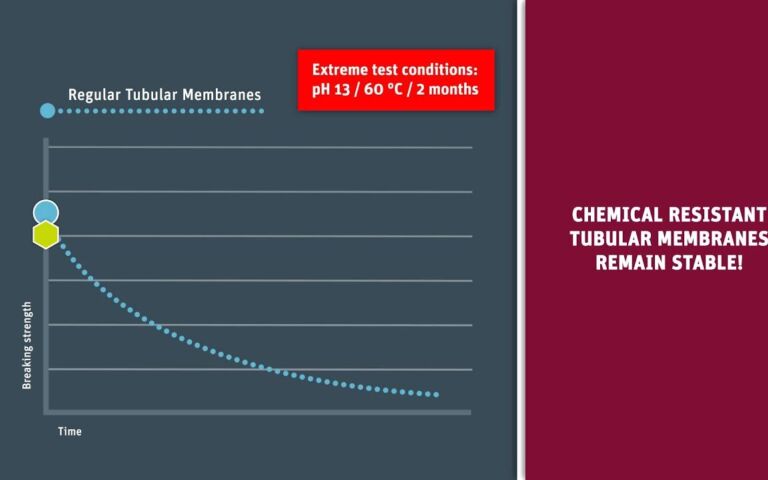

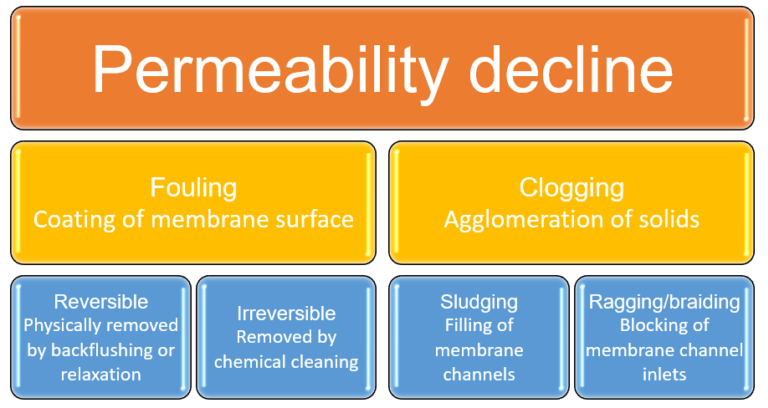

Much of the research conducted in membrane bioreactors has concerned the phenomenon of fouling. Fouling arises when materials either form a layer on the surface of the membrane or plug its pores. Such studies have centred primarily on the characterisation of fouling, and specifically the chemical identification of those constituents which correlate closely to flux inhibition. Studies of this nature are, however, generally unable to distinguish between coating of the membrane service and phenomena relating to the agglomeration of solids (Fig. 1). The latter, variously referred to as clogging, sludging or matting, has received little or no attention from the scientific community, and yet such irreversible deposition of solids is clearly deleterious to MBR operation.

3. Membrane cleaning

Both fouling and clogging cause a diminution of flow through the process. Fouling can generally be substantially removed through the application of a chemical cleaning reagent which is backflushed through the membrane from the permeate side − a procedure known as cleaning in place or CIP. The reagent most commonly used for this duty is sodium hypochlorite, which recovers membrane permeability from organic fouling. Hypochlorite cleaning is sometimes followed by a citric acid clean to remove metal oxide deposits.

However, such remedial measures are much less effective against clogging, since in this case the materials are physically lodged between the membrane surfaces rather than coated onto them. Clogging is only countered by removal of the membrane from the tank and jet cleaning the membrane modules individually.

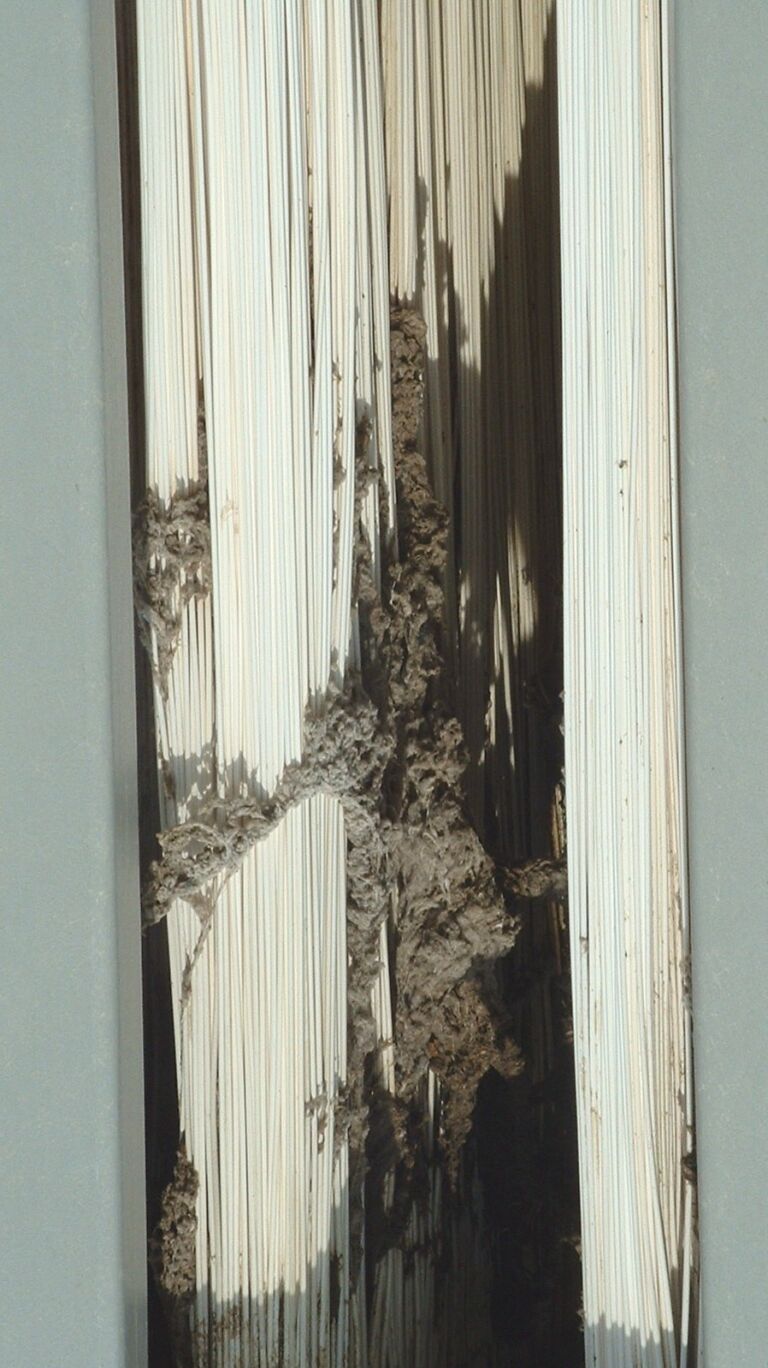

Anecdotal evidence from operation of full scale wastewater treatment works indicates clogging to be a more significant problem than fouling. Clogging within membrane channels (or 'sludging') has been noted in both of the main membrane configurations employed for membrane bioreactors, these being flat sheet and hollow fibre.

Currently, amelioration of clogging is primarily through the rigorous screening of the feedwater. Screens at the inlet remove gross particles which might otherwise accumulate in the membrane tank and clog the membrane channels, as shown in the figures, or in the aerator placed beneath the membrane. The latter provides air bubbles to the membrane, scouring its surface and helping to inhibit the deposition of solids and foulants on the membrane surface.

Clogging of the aerator is therefore extremely deleterious to the process. The standard rating of a screen at the inlet of a classical sewage treatment works is 6 mm. For an MBR the rating ranges from 3 mm for a FS membrane down to 1 mm or less for the HF configuration, with the tendency towards ever tighter screening. The quantities of the screening generated in an MBR process is therefore considerably greater than that produced by conventional sewage treatment, and the management of this waste stream can provide a significant proportion of the operating cost.

4. Ragging

The problem of clogging of membrane channels by gross particles in the MBR is exacerbated by their apparent tendency to agglomerate into long 'rags', which may agglomerate at the channel entrances. Such extensive agglomeration is referred to as 'reconstitution of rags' or 'ragging', and the occlusion of the channel entrances as 'matting'.

Thus, regardless of the rating of the inlet screen, agglomeration downstream of the screens can form particles which are potentially onerous to the process. There is therefore a trend towards installing in-line screens on the sludge recirculated between the membrane and biological treatment tanks, in addition to that at the inlet works. This further increases the quantity of screening requiring management and disposal. There is insufficient historical information available to allow an assessment as to whether such remedial action is effective.

5. Aspects of clogging

Since no published research has been conducted on the phenomena, all information as to its occurrence and control arise from heuristic information. However, there are a number of aspects of clogging which are self-evident:

- The solids agglomeration rate in the channels relates to the rate at which water is drained from the sludge. This in turn is dependent on both the flux and the residence time of the sludge in the membrane channels, since the longer the residence time the greater the extent of dewatering.

- The residence time in the membrane channel is directly related to membrane aeration, with respect to both the distribution of the air bubbles throughout the channels and the overall aeration rate.

- Agglomeration must also depend on the characteristics of the particles, since particles which, for whatever reason, more readily adhere to each other can be expected to agglomerate faster. These may be presumed to be partly related to feedwater physicochemical parameters, since these are known to impact on sludge quality, and the physical nature of the inert solids specifically.

In fact, the same parameters which determine the extent of membrane fouling also similarly influence membrane channel clogging, and the manifestation of the two phenomena (reduced permeate flow) is also the same. It can only be speculated as to whether precisely the same chemical foulants which have been associated with fouling, such as colloidal polysaccharides or proteinaceous materials, are also responsible for particle agglomeration and/or irreversible deposition within the membrane channels.

6. Conclusion

Only further research into MBR particle agglomeration specifically can reveal whether this is the case. However, it is certainly the case that more conservative operation, with lower applied fluxes and/or higher membrane aeration rates, alleviates both fouling and clogging; evidence from full-scale plant suggest that it is those plants operating under such conditions which are subject to significantly less unscheduled intervention. Given the energy penalty incurred by higher membrane aeration rates, it would seem that the industry may in the future have to contend with higher capital costs associated with the larger membrane area demanded to allow operation at lower fluxes.

Whilst clogging is just one of the many challenges to face regarding MBR operation, it is not ubiquitous. Such challenges relate partly to peak loading factors, which are less for larger plants and they in any event seem unlikely to greatly inhibit the growth of the technology. Increasing stresses on global freshwater resources has produced an explosion of interest in municipal wastewater recovery and reuse globally, with MBR:RO being pursued as arguably the most viable low-footprint option for generating high purity water for non-potable use from sewage.

There are already regions of the world (Australia, the Middle East, Singapore and Southern USA) where this process is to be implemented as a lower-energy alternative to seawater desalination − which incurs about double the energy demand. It remains to be seen whether the technology retains its position as the fastest growing membrane-based process for water treatment in the future, and this will partly depend on how the clogging problem is ameliorated. However, it remains the case that without the development of an alternative disruptive technology for wastewater recycling the MBR is likely to be pivotal for this duty for some time to come.